By Dr. Leire Aldaz & Dr. Begoña Eguia (University of the Basque Country)

Economies and societies are undergoing multiple transformations driven by the rapid emergence of digital technologies, the globalising international trade and migration. Indeed, the movement of people, either across an international border or within a state, can be affected by digitalisation and globalisation. The European Union is no stranger to these changes.

Regarding migration, the International Organization for Migration indicates that 281 million people lived outside their countries of birth in 2020, accounting for about 3.6% of the world’s population[1]. 31% of them lived in Europe, and EU-27 hosted 19.4% of the world’s migrants.

The total population in the EU27 has grown by nearly 2% in the last ten years, thanks to the contribution of third-country nationals (TCN), as the volume of the national population has declined during this period. In other words, these migration flows have prevented the EU’s population from being depleted.

The EU has countries with a high migration tradition but also countries that, without such a tradition, have attracted large volumes of migrants over a relatively short period of time, namely Spain and Italy.

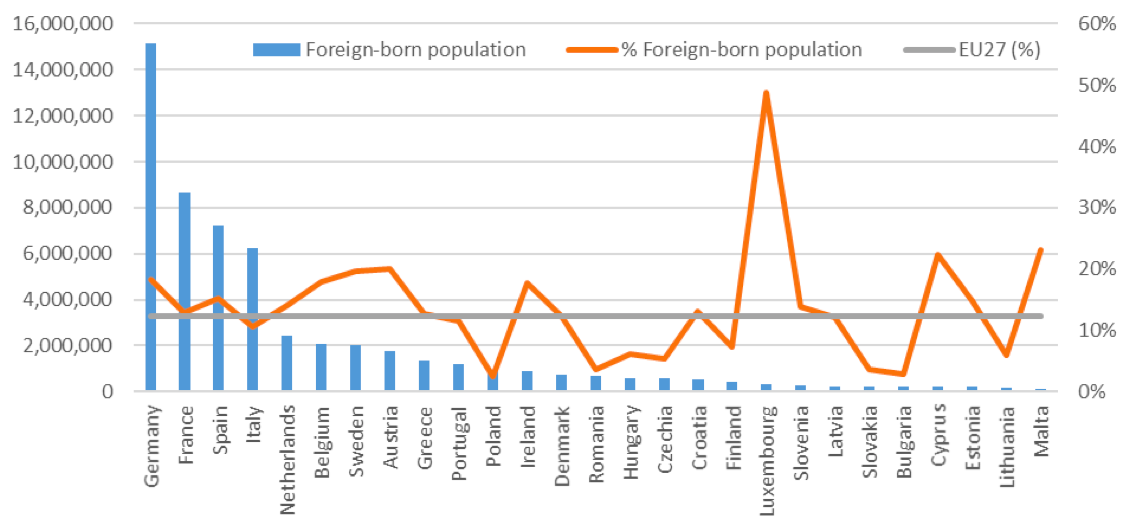

Foreign-born population, 2021, EU-27

Source: Eurostat

In the Figure above, we can observe internal spatial disparities within EU member states in terms of the distribution of immigrants. Some countries receive large numbers of foreign-born people: Germany leads the ranking, followed by France, Spain and Italy. This is not surprising as they are the most populated countries, accounting for 57.6% of the total EU27 population. However, these are not the countries where foreigners have the greatest weight: in Luxembourg,48.7% of the population is foreign-born. It is followed by Malta, Cyprus, Austria, Sweden and Germany. At the bottom of the list are Romania, Bulgaria and Poland, with around 2-3% immigrants.

It is worth noting that around half of these migrants are women.

Another phenomenon related to the movement of people is internal mobility within the EU. In 2021, 4% of the EU-born population resided in an EU member country other than the country of birth.

Both extra-European migration and intra-EU mobility have implications for various spheres of economic and social reality, including, logically, the labour market.

In 2021, 12.2% of the employed population in the EU27 was foreign-born, being almost 45% of them females. According to the origin, 33.2% of the employed foreign-born workers were movers (born in an EU member state), while 66.8% were TCN (born outside the EU).

It is significant that 24% of workers employed in low-skill occupations were migrants, especially, extra-EU migrants. On the contrary, foreign-born workers in high-skill occupations are only 8%.

Furthermore, it should be emphasised that Covid-19 pandemic has severely affected the EU labour market and may also have implications for skills, inequality and the volume and quality of work. More than 2.5 million occupations have been destroyed, and this negative impact has been greater among immigrants. As a result, the participation of employed immigrants in the EU labour market has decreased by one point since 2019.

Understanding the causes and consequences of migration and mobility requires analysing the EU wide perspective. Therefore, the GI-NI project will not only focus on the EU level but will also study in depth different economies with different productive structures: Spain, Germany, Norway, Austria and Hungary.

Currently, the war in Ukraine is causing the arrival of large numbers of migrants in the EU member states. How will it affect European labour markets? Will TCNs increase in all member states? In some of them? In which ones? They may face different barriers in different countries related to language, culture, skills, etc. It will take time to answer these questions.

In addition, the study of trajectories of workers by country of birth will enable the design of policies to be able to anticipate new future scenarios.